Creating impact from Men, Poverty and Lifetimes of Care

‘Men, Poverty and Lifetimes of Care’ (MPLC) was funded by the Leverhulme Trust between October 2014 and June 2018 and examined men’s care responsibilities, support needs and patterns of care across the life course in low income families in the UK. Drawing predominantly on data generated from semi-structured interviews with twenty-six men in different generational positions living in a Northern city in England, the research has explored the social and relational dynamics of low-income family life, over time, from men’s perspectives. The men interviewed were young fathers (aged 25 and under); mid-life, predominantly single fathers with primary care responsibilities (aged 25 – 45); and kinship carers (uncles, grandfathers and a great-grandfather), who were providing support for family members in contexts of state intervention.

Men in low income families are very rarely given a voice in research about family life and poverty and are often vilified as absent, feckless and/or disinterested in family life. The aim of the print exhibition was to speak directly to these narratives and to challenge them by giving men a voice about their experiences of care-giving and about the very real challenges that they face on a day-to-day basis while also trying to do the best by their children.

The exhibition would not have been possible without the help of Katie Smith who helped to design the prints. You can learn more about Katie and the work we have done together in what follows…

A bit about Katie Smith…

Katie Smith describes herself as a socially engaged artist with a research based approach to her practice. She predominantly works with marginalised communities and is a passionate advocate of enquiry-based learning. Katie uses a variety of creative media from pinhole and Polaroid photography to collage, low-tech print and stitch to engage with and stimulate social processes.

This year in addition to working with Anna on developing an exhibition from the findings of MPLC, Katie has also been collaborating with artist Kate Genever. As Smith-Genever, the pair have been awarded Arts Council funding to explore resilience as a concept within Ash Villa, an inpatient unit for young people experiencing acute mental health issues (the project is supported by MMU, Axisweb and York Teaching Hospital). They are also amongst 100 UK women artists commissioned by Artichoke and 14-18 NOW to create a centenary banner for PROCESSIONS, a mass participation artwork to celebrate one hundred years of votes for women.

You can learn more about Katie’s work here: www.katiesmithartist.co.uk

Our work

Katie and I met towards the end of 2017. We bonded immediately over a shared passion for tea, cake, and the desire to think creatively about how we might work towards a more inclusive society by speaking directly to, and challenging, broader structures of inequality and power, using research. We decided to explore ways in which we could work together to produce creative outputs from the MPLC study that would have the potential to raise awareness about men’s capabilities to engage in care across the life course, albeit in often challenging financial circumstances and with limited state support.

Katie thought that traditional letter press prints would be the best medium for this work not least because each design is completely unique and can’t be replicated, much like the narratives of the fathers in this research. Once designed, she worked closely with the Small Print Company who printed the posters (see images below). The prints were displayed for the first time at an end of research seminar called ‘Researching the dynamics of low income family life’ held at the University of Lincoln on Thursday 14th June 2018.

The story of the research and the exhibition

The narrative begins with a focus on male kinship carers. While the older of the men in the study, their narratives make visible and exemplify both men’s capabilities and intentions to provide care for their family members and also the complex challenges they face in securing and sustaining these responsibilities. The quotes that follow reveal the ways in which fathers make sense of their role and of the challenges of their otherwise invisible familial responsibilities, including how they respond to the personal circumstances and contexts that render them, and their families, vulnerable. Narratives of loss are prevalent but so to are examples of emotional intelligence whereby care for children, is prioritised over and above personal challenge and prejudice. Finally, the story evolves to explore the significance of locality, community and the histories of place in men’s narratives that impact on and explain, the variety of ways in which they navigate low income life. Engagement in behaviours of harm, like alcohol dependency and violence are intimately linked to the social isolation and violence of low income localities and can serve to exacerbate the vulnerabilities of fathers and undermine their care giving efforts. Yet localities also offer important spaces for community, support and belonging that are increasingly being stripped away under the conditions of austerity.

Male kinship care

Kinship care is a term used by local authorities and in official documents to define family or friend’s carers to children when parents can no longer provide adequate care (Grandparents Plus, 2018; Hunt, 2018). Six of the men interviewed for the MPLC study were kinship carers, including one uncle, four grandfathers, and one great-grandfather. Despite the reported benefits of raising children in kinship care, recent evidence suggests that three quarters of all children in kinship care in the UK live in a deprived household (Wellard et al. 2017). Current evidence about kinship carers is primarily based on the experiences of women (see MacDonald et al. 2016). Not only are women more likely to be primary care givers, they are also particularly vulnerable and at risk of impoverishment (see also Bennett and Daly, 2016), ill health and poor housing conditions (Hunt, 2008). However, we also know that kinship carers are far from a uniform, homogenous population. They vary greatly according to their characteristics, roles and statuses (MacDonald et al. 2016). The MPLC study offered new insights into men’s gendered experiences of kinship care and associated financial precarity.

Image gallery and cases

(Please note that all names are pseudonyms to avoid identification of project participants)

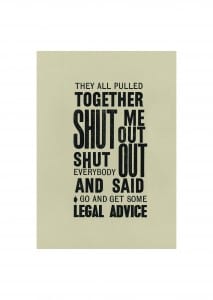

Sam is 51 years old. He is father to five children and has a Special Guardianship Order for his grandson, age 4. Securing this order for his grandson was very challenging. Sam’s son, the father of his grandson, has learning difficulties. Sam considers the mother of his grandson to be ‘streetwise’ and claims she had her son to secure housing and welfare support. She was also a product of the care system and both she and all her siblings are care experienced. Sam’s grandson was born prematurely, weighing just 1 lb 11 oz. This vulnerable baby was released from hospital into the care of his mother and grandmother. He later presented with signs of abuse not long after and returned to hospital. Sam, who had been expressing concerns to social services about his grandson on a daily basis, describes a complicated and drawn out process in which he tries to raise concerns and secure primary care responsibility. He describes feeling shut out and pushed towards the justice system. Social services become more helpful after a successful application in court but remain cautious, which he sees as positive and wishes they’d done when his grandson was released to the maternal family. His example demonstrates how kinship carers have to rely heavily on the justice system rather than the state to support them.

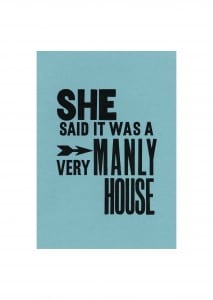

Sam suggests that the caution evident in interactions with social services during the assessment process became intrusive, reflecting a distinct gender bias. While Sam is the most resourced and capable individual to care for his vulnerable grandson, during one assessment by a social worker in his home, she raises concerns that his house is “manly”, lived in as it is by Sam and his son and furnished to their tastes. Such comments require challenge, especially given that where men are deemed incapable carers as a result of gender, the consequences can be extreme i.e. children might enter the care system. It is essential that men are considered and accommodated in care decisions and gender bias is addressed.

Complex family structures and financial precarity

Theo is 39 years old. He is a father and stepfather to two children (aged 12 and 2). At the time of interview he was also providing informal kinship care to his niece, great-niece (aged 16 and one years old) and nephews (aged 19, 8 and 5) following the death of his sister and of his father 16 months prior to that. He has left employment to provide care for his two youngest nephews in his sister’s rented accommodation, one of whom has suspected learning difficulties. While a decision is being determined about whether he will obtain a care order for his two youngest nephews, he is spending five days a week in his sister’s home that he is paying for out of his life savings and with some money borrowed from his mum, who is 61 years old, has Crohn’s disease and is incapable of providing support. He is spending weekends with his partner, son and stepson at their privately rented home when he can. He feels like he is being forced by social services into securing a Special Guardianship Order because it is cheaper for the local authority. While all this is happening (over the school summer holidays) he has just £3.26 a day to support all five children.

Theo’s quote is indicative of the pressures that individual families experience in the process of decision-making around the appropriate placement of children. Theo is the most resourced and capable person in his family and is the best placed to ensure that the two younger children remain in the family. Yet to do so, comes at an immense financial and personal cost for him. Despite trying to keep these grieving children together and in the family, while also grieving himself, he is also being plunged into poverty and forced to split his time and resources between two households. Financial and emotional state support is severely lacking and is inadequate for addressing the complexities of this family’s structure and circumstances.

When financial support ends

Pearce is 57 years old and is married. He and his wife have a Special Guardianship Order for two of their grandchildren, who were neglected by his son and partner. When his own children were young he was employed as a lorry driver; his wife didn’t work until their children were grown up. Pearce and his wife decide that Pearce should leave his job to provide care for the two grandchildren while his wife remained at work. He describes becoming a kinship carer as a huge learning curve and one that has made him appreciate the care his wife provided their children since their divisions of labour have reversed.

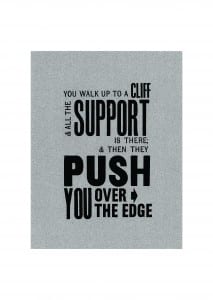

In a later interview he reveals that without warning, the local authority has stopped the financing attached to the Special Guardianship Order. He is now looking for flexible employment to avoid childcare fees and so that he can provide care to the children during holidays. He is aware that his options are limited both by his age (he is near retirement) and lack of flexibility in the work he is able to secure. He describes the withdrawal of financial state support as like being pushed over a cliff edge.

Further information about kinship care, including support for kinship care is available via the Grandparents Plus and Family Rights Group websites.

The emotional dynamics of an invisible role

- Low income fatherhood remains relatively invisible and is a role that produces vulnerability for men, and distinct emotional challenges,

- This is linked to the diverse circumstances and backgrounds they report.

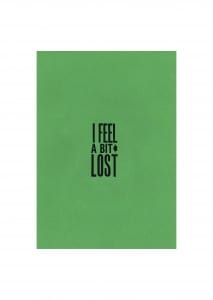

- The notion of loss, and of feeling lost, was a particularly powerful narrative for the young fathers (aged 25 and under) in the study. This was linked to uncertainty about how to manage the multiple responsibilities of fatherhood in early adulthood while also trying to work through the longer-term effects of otherwise chaotic childhoods linked to intergenerational experiences of deprivation.

Joe is a young father. He is 22 years old and has two children by two different partners. His dad, who was violent to his partner and children, left home when Joe was 15 years old. Joe’s mum then ‘kicked him out’ when he was 16 years old when his behaviour, linked to the locality in which he lives, becomes problematic. He has spent some time in prison linked to drinking, violence and anger issues. He found the break up of his parents very difficult but his stepfather advised him to lock these emotions away. He now wants to seek counselling because he does not find that easy to do. Joe recognises that he needs to look after himself first before he can look after his children properly but palpable in his narrative is a feeling of having lost his way and being unsure how he can balance his responsibilities for his children while also securing stable housing and employment and nurturing his own well-being.

Older fathers

- In contrast, some of the older fathers in the study had developed a more sophisticated language for expressing their emotions and their philosophies for raising children.

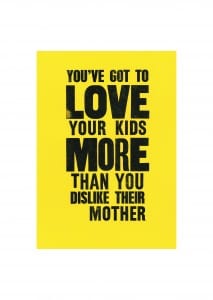

Shaun is 38 years old and has primary care responsibility for his two young daughters. He is unemployed and so raises his girls using social support. Shaun has had a chaotic childhood and early adulthood. His parents divorced during Shaun’s childhood where he spent some time living with his maternal grandmother as a result. Despite being close to his mother, he was abused by his stepfather. He therefore leaves home and lives in hostels, where he becomes addicted to heroin. Following a freak accident he decides to get clean. He finds stable but low paid employment as a carer and then a DJ and meets the mother of his children. Both Shaun and his partner become alcohol dependent but this escalates into violence towards one another that is witnessed by the children. When the relationship breaks down, social services intervene and award Shaun custody of the girls, determining the mother’s ongoing alcohol dependency to be more problematic. In reflecting on his parents’ relationship and the way that they put their disagreements ahead of the welfare of Shaun and his brother, he explains his philosophy for managing his relationships with his ex-partner and ensuring a stable upbringing for his girls. As an older father, Shaun is attuned to the emotional needs of his children, albeit while managing the stresses of raising his children alone on a low income.

Strategies for coping

Despite being a study that focused on men’s care responsibilities and social and familial relations, the majority of men interviewed made sense of their experiences in the context of the low-income localities and their communities.

- As well as providing care for their families, they were also negotiating the distinct challenges of these contexts. The fathers responded to these challenges in several different ways.

- For some, providing care, especially as single fathers, isolated them and led to dependencies on alcohol and other stimulants. Others responded with violence.

- Over time however, community spaces like community centres take on a renewed significance and for some, offer the companionship and resources required to survive as an older man in low income localities.

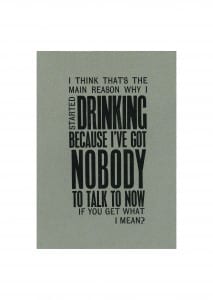

Joseph is 49 years old and has primary responsibility for his two daughters, aged 17 and 14. He is divorced and has diabetes neuropathy, which has disabled him. Despite being physical immobile and being cared for by his 14-year-old daughter, he has been deemed fit for work at a work capability assessment. Joseph was especially close to his own father who was his main confidant. When his father died, Joseph became socially isolated. This was the result of a combination of pressures including his divorce, his care responsibilities for two young daughters as a single father, unemployment, his disability and the loss of his father lead, all of which lead to a period of alcohol dependency in order to cope.

He eventually stopped drinking to better support his daughters but remains lonely.

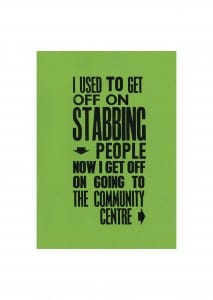

One of the more poignant quotes came from Graham. Graham is 45 years old and is a non-resident father. Both of his children are now ‘looked after’. Graham is unemployed and has learning difficulties, but spends a lot of his time at a community centre near his home. Here he describes how the mechanisms for survival in his locality have changed for him over time. Where he once engaged in violent behaviour in order to obtain the resources necessary to provide for his family, he now engages in community life at the local community centre. As an older man in the locality, this provides a source of friendship, belonging and the ability to acquire key resources and skills. Community spaces such as these however are increasingly at risk under austerity.

Exhibition booklet

An exhibition booklet, based on each of the cases above, has been created to sit alongside the exhibition. A key intention for producing the prints that are presented and explained in this booklet is that they give voice to men in low income families who are usually marginalised and vilified by policy makers and the media (Neale and Davies, 2015) and constructed as largely absent, feckless and disinterested in family life. The quotes presented have been carefully selected to challenge these ‘commonsense’ ideas, by foregrounding men’s voices. This has been done to demonstrate the capabilities of each of these men to participate in family life, while also raising awareness of the specific challenges they face, in a way that does not contribute to this vilification.

A copy of the information leaflet about the exhibition can be downloaded here: Creating impact from Men, Poverty and Lifetimes of Care